Signin with Google

Signin with Google Signin with Facebook

Signin with Facebook

Culture,Literature

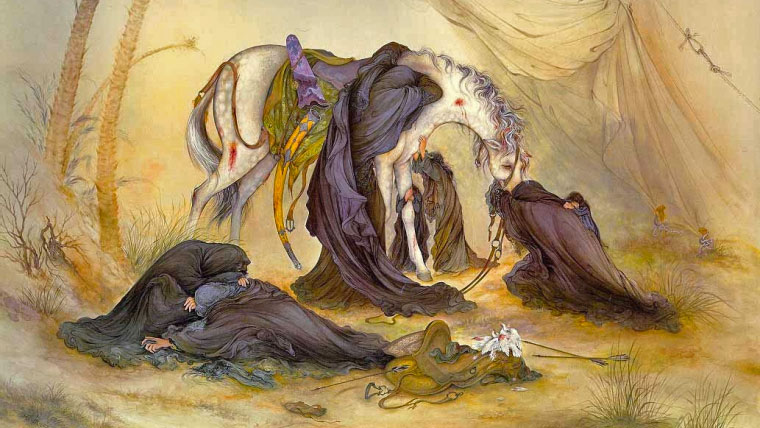

Culture,LiteratureThe Persian Miniature, a Detailed Eden

When the Phoenix was born

It was about 1524 when Shah Tahmasp, the Safavid ruler, summoned the greatest masters of calligraphy, illumination, painting and book biding from all over the country. They all ought to work at the royal atelier located in the Safavid capital of Tabriz, and create the most opulent illuminated version of "The Persian Book of Kings". The completed edition of this royal manuscript contained 258 exquisite Persian miniature illustrations, was written in fine Nasta'liq script, bounded sumptuously, covered in a jewelled coat and finally presented to Sultan Selim II of the Ottoman Empire as a gift from Shah Tahmasp.

Apart from its historical and literary significance, this royal manuscript which is now known as The Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp is of high aesthetic importance as well. It is believed to be the culmination of the art of Persian Miniature.

The Messenger of art

According to historical sources, Mani or Manes(216–274 AD) the prophet and founder of the ancient Persian religion of Manichaeism was an artist and Arzhang, the religion's holy book included many drawings and paintings illustrated by the prophet himself. Although not much has remained from Mani's illustrations, many experts believe that the Persian style of miniature painting is a descendant of Manichean art.

Islam and Persian Miniature

Due to some religious reasons which are not directly mentioned in the Quran, the Islamic culture has always practised a kind of prohibition against visual arts such as painting and sculpture (specifically creating images of living beings). Instead, it has mostly focused and prospered in other categories of art including calligraphy, architecture, ceramic, tiling and pottery.

Yet, despite all of the restrictions, the art of Persian Miniature Painting became widely prevalent, precisely during the Islamic Period, starting from the 13th century till the 16th century when it almost reached its zenith.

A new tradition rose from the ashes

This exquisite style of art dated back to the late Sassanid era and had been forgotten for a long time was revived by the devastating Mongol invasion of Persia in 1219. Although the new foreign rulers of the country brought grave destruction and trauma to themselves, they had a significant effect on flourishing Persian miniature by introducing other genres such as Chinese miniature -which was already a developed tradition- to Iranian artists.

The interest of the ruling court in commissioning miniature artists accompanied by the skill and creativity of Persian miniaturists, resulted in the significant development of this art in Persia to the extent that during the 15th and 16th centuries, Persian miniature became the chief influence on other Islamic miniature styles including Ottoman and Mughal miniature.

Consequently, several new schools emerged in different corners of the Empire, namely Shiraz School, Tabriz School, Herat School and Isfahan School as the most influential ones and from each school rose prominent artists such as:

- Kamāl ud-Dīn Behzād (1450-1535), the head of the royal atelier in Herat in the late Timurid era

- Reza Abbasi (1565-1635), the leading artist of the Isfahan School

- Agha Mirak (1520-1576), one of the prominent miniaturists of Tabriz School who also significantly contributed to illustrating the Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp

A fancy art collection of one's own

Before the prevalence of Persian miniature paintings, illuminating book pages with non-figurative patterns and geometrical/natural motifs was already a common tradition in the Islamic art of bookmaking. This elegant tradition of adorning books was taken to a new level when bookmakers started to include both illuminations and full-page miniature illustrations in books, like the Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp.

However, the popularity of these delicate pieces of painting did not stop there and later creating single-page miniature illustrations (mostly portraits, scenes of lovers in nature, etc.) and collecting them in a private album called Muraqqa, became a favoured luxurious practice among wealthy individuals.

Various styles, united techniques

As previously mentioned, various styles were developed in different cities, while almost all of them shared the same techniques and features. For instance, the bright colours, round faces, detailed designs of fabrics and carpets, mountainous landscapes, and perspective-less and shadow-less images are common features amongst all styles of Persian miniature paintings.

And in terms of technique, the main work was usually carried out by two artists. The senior miniaturist was in charge of drawing the outlines, and the less experienced artist was responsible for colouring the drawings. In some cases, different artists worked on border illuminations and faces.

The materials used for creating Persian miniatures were also the same in all schools:

- Paper: selecting the finest kind of paper, was considered an essential first step. According to historical documents, Persian miniaturists avoided using white papers. Thus, they used to dye pieces with various natural substances including flowers, fruit juice, herbs and gold/silver dust. Samarkand was one of the famous producers of fine papers.

- Colour: the colours used in the creation of Persian miniatures were mostly organic pigments extracted from herbal and mineral substances such as lapis lazuli, red ochre, malachite and madder root. Gum Arabic and egg yolks were also two common materials used to bind colours.

- Gold: the use of gold is significant in Persian miniature paintings, mostly used for illuminating page borders.

The fall of Persian Miniature

Although this unique style of painting enjoyed centuries of high popularity, its long life almost came to an end around 1540 when Shah Tahmasp, a former patron of miniature lost his interest in this art and stopped commissioning artists. As a result, the miniaturists who used to work at the royal atelier of Tabriz were forced to travel to other cities where they could continue working as miniature artists

Persian Miniature in contemporary Iran

Miniature Paintings are still popular among Iranians. Following the old tradition of illuminating manuscripts, modern Iranian publishers also include copies of both old and new miniature illustrations in printing classic works of literature such as "The Divan of Hafiz" and "The Quatrains of Omar Khayyam".

Fortunately, this elegant tradition of painting has been preserved by the efforts of various contemporary artists—the most prominent of them, Mahmoud Farshchian (1930-present) who is a master of the Persian miniature. Hossein Behzad (1894-1968) is another master of Persian miniature who had a significant role in reviving the Persian style of miniature painting.

The Saadabad complex locates in the north of Tehran, the capital of Iran, hosts two museums of Miniature works and paintings of masters Farshchian and Behzad.

By Nazanin Moayed / TasteIran