Signin with Google

Signin with Google Signin with Facebook

Signin with Facebook About Iran

About IranIslamic Architectural trace in Iran

There is a vast amount of literature about Islamic architecture, but generally speaking, what is it that makes a building or a façade architecturally Islamic? One single and probably most important factor that stands out is that it was built sometime after the 7th century and probably somewhere in the Middle East.

The Prism of light scatters divinity

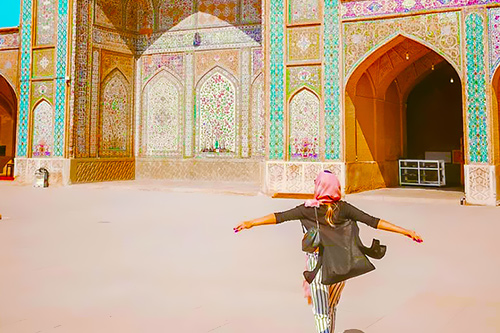

One of the key elements in Islamic architecture that from its religious background it shares with Zoroastrian, Jewish and Christian traditions is the light and the use of architectural elements to highlight the sacred meaning of light to those dwelling in a specific building or structure. In Iran, like nowhere else in the Middle East, this found particular expression in the Iranian stained-glass technique, as attested by numerous mosques and old traditional houses across Iran. Easily the most notable example is Nasir Al-Molk Mosque, also known as Pink Mosque, in Shiraz. As a manifestation of God’s existence and mercy, the light shining through the stained-glass windows of the mosque’s winter prayer hall (shabestan-e gharbi) is soft and gentle. It comforts the eye, creating a unique spiritual atmosphere and space of peace and calm.

In Islamic architecture, the actual window plays an important role and not only for light purposes. Social norms in Islamic societies dictate the separation of sexes and emphasise privacy of one’s household and family members, particularly female.

A beautiful separation

Shobbak or more locally Moshabbak windows, often with blue tile glazing, were used to prevent visitors from looking into the daruni (internal quarters), whilst letting those inside the house observe the strangers at their leisure without revealing their identity. A convenient and much-practised way for ladies to study their potential suitors from inside their private space. There are many examples of shobbak windows across Iran. Still, a particularly fine one is in Esfahan, in the Moshir Al-Molk Historic House in the vicinity of the UNESCO-listed Naqsh-e Jahan Square.

Islamic tradition has had a significant influence on the architectural arrangement of a private Iranian dwelling. The house in the post-7th-century Iran has come to be divided into two sections, daruni (meaning inside) internal quarters for the family members and biruni (meaning outside) for guests and visitors. Each unit would traditionally consist of several rooms grouped around a courtyard with a cosy howz (pool) or howzcheh in its diminutive form, but this tiny pool so frequent in Iran is a remnant of a more ancient Iranian garden arrangement, rather than an element in Islamic architectural style. Although much has changed, including the style and building materials, many of the buildings, especially in rural Iran, have more or less retained the daruni and biruni layout.

Safe under the crossed-arch walls

In the actual mosques in Iran, where Islamic architecture has taken a very distinctive development in this regard, it is the four-Ivan (meaning quadrangle-vaulted hall in Persian) plan with a central courtyard in the middle that stands out. While most Iranian houses of worship, unlike its counterparts elsewhere in the Islamic part of the Middle East, have four-ivan plan, one of the finest examples of this architectural tradition is the UNESCO-listed Masjed-e Jame(congregational mosque) in Esfahan.

The roots of this fourfold arrangement trace back to the original Persian garden design, known in Persian as Chahar-bagh (meaning four gardens). Chahar-bagh’s symmetrical and bordering sheer perfection arrangement has proven so popular over the centuries that many classic gardens in India and elsewhere in the region follow the same design. And from Chahar-bagh to one of the finest examples of Islamic architecture –four-ivan plan – to small howz, visitors to Iran never stop feeling amazed at the architectural design surrounding them here.